Yup listening to sentences not individual words. It would be like learning French words then trying to remember which one is La and Le individually.

Krashen + 1 still applies to this day. I’m practically fluent and I looked at a book for maybe only 2 days. To be honest I self learned a few words consciously but most were acquired not learned. The conscious learned ones were the ones which were in the top 100 most commonly used Chinese words, then I just tried using them…

It’s funny, if I’m trying to learn a new word or phrase that someone has said to me in Mandarin, and I don’t catch the tones, the speaker can always tell me which tones. Yet, when I have the same experience with a Taiwanese word/phrase, they can never explain which tones…they always just keep repeating it. I guess that’s the “keep listening” that you recommend.

Yep, Krashen

Because they haven’t had explicit schooling in it, so must people won’t know the numbers of the tones even, and have no reference for explaining it. They just learned it like native speakers learn languages, without thinking about any of that stuff.

The basic idea is that this is how native speakers learn, and the most effective way to learn a new language as well. Glossika has a pretty good program, they have Taiwan Minnan

Why not sound like what I am? ![]()

Is it possible in Taiwan to get a job, specifically a computer tech job, with no Chinese whatsoever and just ‘pick up’ the language?

After six weeks in Taiwan I started with nothing and I left with 你好,謝謝,人,火,火龍果, 再見 and can count to 5 ![]()

I’ve still never really understood why almost nowhere in Taiwan seem to use Krashen’s and Chomsky’s ideas. They seem to input so much money and get so little return on it. I don’t 100% go along with all his philosophy but it seems that in all my years here I’ve almost never heard of a school that does not teach grammar rules and almost always in great detail. I think Krashen visited Taiwan and his ideas were not well received with the education minister of the time saying his methods were not suited to Asians or something along those lines.

The Altaicization of Northern Chinese

https://books.google.com/books?id=jdYUAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA76&dq=Hashimoto+Mantaro+Altaicization&hl=en&ei=hnz7S5aZHIKBlAfqtp3KDw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CC4Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Hashimoto%20Mantaro%20Altaicization&f=false

harsh toke…

Learning Taiwanese tones are the same as with Mandarin, you learn them intuitively with time. It just takes a lot more time. Seems like Glossika could speed the process. But the payback on the effort is huge. Taiwanese is chock-full of hilarious 俗語’s, ribald jokes, creative swear words, subtle and colorful stuff that just doesn’t seem to get said in respectable Mandarin. My neighbor’s bulldozer slid off the side of the hill into a muck pond last week. I watched and harassed him for an hour and learned so many great new words! Mandarin is important, I need it for technical and engineering stuff. But Taiwanese is a hoot. Harder to learn but worth it. After Mandarin and if you have time. Highly recommended.

hilarious 俗語

I still remember the first one someone taught me, they thought it was hilarious to hear me say it. tua-tng ko sio-tng

Sorry, didn’t mean it to imply that swear words were a reason to learn Taiwanese. You can learn a lot about traditional Taiwanese culture by learning Taiwanese (and I assume Hakka).

I think 俗語’s are way more fun and interesting than 成語’s (which seem to mostly be based on stuffy historical stuff). It’s the real reason I started on Taiwanese.

My Taiwanese sucks, but I’ve always liked the 歪嘴雞食好米 one.

Ok, I feel like I need to rehash some of the things I’ve mentioned on forumosa before.

As for being archaic, Mandarin Chinese is technically only at most 250 years old. Even in 1815, when Robert Morrison wrote the first English-Chinese dictionary most people in Beijing were still speaking the Chinese Koine, which was based on Nankinese, and was much closer to Middle Chinese that was spoken since the Tang dynasty. In comparison, English is a much older language. At least I am confident we can understand Robert Morrison from 1815 fairly well.

When the Manchu sacked Beijing in 1644, people of Beijing spoke the Mandarin (官話) of the time, the Chinese Koine, which was based on the Nanjing accent, since Ming was founded by a group of people from the south, and the first capital of Ming was Nanjing.

The Nanjing accent, which is a part of the Wu branch, retained many features of Middle Chinese. The Chinese Koine at the time still retained most checked (entering) tones, and in many ways to was more similar to Cantonese and Taigi than Mandarin today.

When the Ming dynasty collapsed, Europeans are already in Asia. In 1644, the Dutch were still operating from Taiwan. There have been a couple of prominent European missionaries in Ming court, such as Matteo Ricci, Ferdinand Verbiest and Johann Adam Schall von Bell. Many of them transitioned over to work for the Manchus when they took over.

Many early romanizations of Chinese cities were made by these early christian missionaries. They’ve also left extensive record of Mandarin spoken in Beijing during the interim period between Ming and Qing dynasties.

As I’ve mentioned in my previous post, even in 1815 most people in Beijing still spoke the Chinese Koine in official settings, even though plenty of them spoke the predecessor of today’s Mandarin in private.

This is because the Manchurians forced relocated Beijing’s Han residence within 5 km of the imperial city, and made the so called “inner city” exclusive to Manchurians. However, those in the inner city soon found out that they had to pick up Chinese to conduct daily business, and soon developed their own heavily Manchurian influenced Pekingese flavor. The inner city Pekingese and the outer city Pekingese was divided by caste. The Manchu and elites living in the inner city spoke a Manchurian-Chinese pidgin. Most people living in the outer city still spoke the old Pekingese. This was still the case when Robert Morrison wrote his Chinese dictionary in 1815. Plenty of Manchu officials stationed around the country came straight out of the inner city. They began influencing people outside of Beijing to pick up the inner city Pekingese as the new official language. Overtime, people living in the outer city started to switch to the language of the higher caste to gain more prestige. That’s how we ended up with a full Mandarin takeover in areas around Beijing by the early 1900s.

The influence of Manchurian and Mongolian is clear in today’s Mandarin. Using 的 or 底 as the possessive marker is obviously borrowed either from Manchurian or Mongolian, which uses the -d or -de suffix to denote locative or dative case. That somehow is borrowed into the inner city Pekingese to function as the possessive marker.

The original possessive in Middle Chinese would be 其 (kê), which became 嘅 (ge3) in Cantonese, 個 or 个 (ke) in Hakka, and 个 or 兮 (ê) in Taigi.

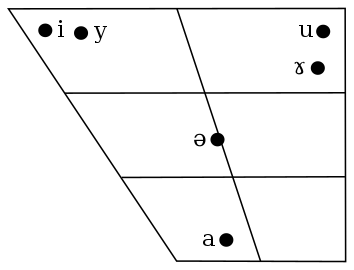

Manchurian language lacks the /e/ vowel sound.

Manchurian vowel chart.

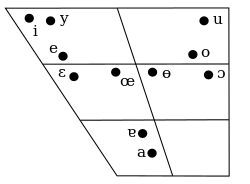

Compare that to Mandarin’s vowel chart.

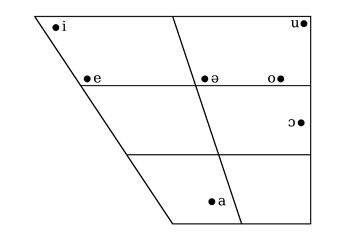

Now compare that to languages more similar to Middle Chinese, such as Cantonese and Taigi, both of which have the /e/ vowel.

Cantonese

Taigi

Other phonology influences include introduction of /f/ fricative to Chinese. This sound doesn’t exist in Middle Chinese.

Some other Mongolian/Manchurian influences in today’s Mandarin aside from the phonological changes and the possessive marker are as follows:

-

Using 白 to describe getting something for free unfairly. For example 白吃白喝. From baibi, which means empty, or to no avail. This usage was probably borrowed from Mongolian. I think it was first attested in Ming novels.

-

挺 as a way to say very. For example: 挺好的. Borrowed from Manchurian ten, meaning very.

-

馬馬虎虎 as Chabudou attitude. Borrowed from Manchurian lalahuhu.

-

巴不得 as can’t even. Probably borrowed from Mongolian. It is similar to the Manchurian word bɑhɑci with the same meaning. Earliest usage seen in Ming novels.

-

彆扭 as in awkward. Borrowed from Manchurian ganiu, meaning special. No attested usage before the Qing dynasty.

-

邋遢 as in unkempt. Likely borrowed from Mongolian. Manchurian has a word lata with the same meaning. Earliest usage was late Ming, early Qing.

There’re tons more… but I doubt anyone is reading by this point…

There’re tons more… but I doubt anyone is reading by this point…

Au contraire. Fascinating stuff!

巴不得 as can’t even.

That’s not can’t even, that’s more like would rather.

outer city Pekingese

I wonder what that was like. Any dialects supposed to be closer to it or other research?

Difficult to learn but possible.

There’s levels of fluent-ness (my word).

Not hard to get to the daily life level that covers most of every day needs and communication. You might have to pick through writing/reading with the help of Pleco and Translate but certainly do-able. This level makes living in Taiwan a breeze

Then there are other levels. This is where it starts getting serious.

Ever attended local training, educational sessions, or meetings? Well now we’re talking a whole new level of toughness. You’d need to spend all day for years and years to even scratch the surface.

Slide after slide crammed with Chinese characters. The brain shuts down. You might start picking through that first few characters only. After 30 min you’re not registering anything the speaker is saying.

People throw around the word “fluent” loosely.

I cringe when locals do the “你中文很好” thing. No really it’s not, and you’re pissing me off saying it