Ok, I feel like I need to rehash some of the things I’ve mentioned on forumosa before.

When the Manchu sacked Beijing in 1644, people of Beijing spoke the Mandarin (官話) of the time, the Chinese Koine, which was based on the Nanjing accent, since Ming was founded by a group of people from the south, and the first capital of Ming was Nanjing.

The Nanjing accent, which is a part of the Wu branch, retained many features of Middle Chinese. The Chinese Koine at the time still retained most checked (entering) tones, and in many ways to was more similar to Cantonese and Taigi than Mandarin today.

When the Ming dynasty collapsed, Europeans are already in Asia. In 1644, the Dutch were still operating from Taiwan. There have been a couple of prominent European missionaries in Ming court, such as Matteo Ricci, Ferdinand Verbiest and Johann Adam Schall von Bell. Many of them transitioned over to work for the Manchus when they took over.

Many early romanizations of Chinese cities were made by these early christian missionaries. They’ve also left extensive record of Mandarin spoken in Beijing during the interim period between Ming and Qing dynasties.

As I’ve mentioned in my previous post, even in 1815 most people in Beijing still spoke the Chinese Koine in official settings, even though plenty of them spoke the predecessor of today’s Mandarin in private.

This is because the Manchurians forced relocated Beijing’s Han residence within 5 km of the imperial city, and made the so called “inner city” exclusive to Manchurians. However, those in the inner city soon found out that they had to pick up Chinese to conduct daily business, and soon developed their own heavily Manchurian influenced Pekingese flavor. The inner city Pekingese and the outer city Pekingese was divided by caste. The Manchu and elites living in the inner city spoke a Manchurian-Chinese pidgin. Most people living in the outer city still spoke the old Pekingese. This was still the case when Robert Morrison wrote his Chinese dictionary in 1815. Plenty of Manchu officials stationed around the country came straight out of the inner city. They began influencing people outside of Beijing to pick up the inner city Pekingese as the new official language. Overtime, people living in the outer city started to switch to the language of the higher caste to gain more prestige. That’s how we ended up with a full Mandarin takeover in areas around Beijing by the early 1900s.

The influence of Manchurian and Mongolian is clear in today’s Mandarin. Using 的 or 底 as the possessive marker is obviously borrowed either from Manchurian or Mongolian, which uses the -d or -de suffix to denote locative or dative case. That somehow is borrowed into the inner city Pekingese to function as the possessive marker.

The original possessive in Middle Chinese would be 其 (kê), which became 嘅 (ge3) in Cantonese, 個 or 个 (ke) in Hakka, and 个 or 兮 (ê) in Taigi.

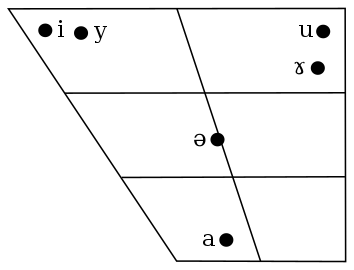

Manchurian language lacks the /e/ vowel sound.

Manchurian vowel chart.

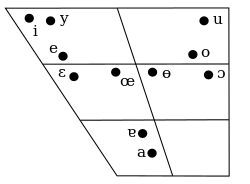

Compare that to Mandarin’s vowel chart.

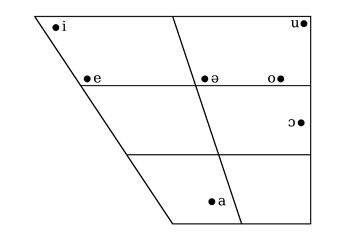

Now compare that to languages more similar to Middle Chinese, such as Cantonese and Taigi, both of which have the /e/ vowel.

Cantonese

Taigi

Other phonology influences include introduction of /f/ fricative to Chinese. This sound doesn’t exist in Middle Chinese.

Some other Mongolian/Manchurian influences in today’s Mandarin aside from the phonological changes and the possessive marker are as follows:

-

Using 白 to describe getting something for free unfairly. For example 白吃白喝. From baibi, which means empty, or to no avail. This usage was probably borrowed from Mongolian. I think it was first attested in Ming novels.

-

挺 as a way to say very. For example: 挺好的. Borrowed from Manchurian ten, meaning very.

-

馬馬虎虎 as Chabudou attitude. Borrowed from Manchurian lalahuhu.

-

巴不得 as can’t even. Probably borrowed from Mongolian. It is similar to the Manchurian word bɑhɑci with the same meaning. Earliest usage seen in Ming novels.

-

彆扭 as in awkward. Borrowed from Manchurian ganiu, meaning special. No attested usage before the Qing dynasty.

-

邋遢 as in unkempt. Likely borrowed from Mongolian. Manchurian has a word lata with the same meaning. Earliest usage was late Ming, early Qing.

There’re tons more… but I doubt anyone is reading by this point…