Reviving this thread to link a retrospective reconsideration of Chen’s controversial legacy by Nicholas Haggerty at the New Lens. This is the first of a two-part article. It’s well worth reading.

The Troublemaker: Chen Shui-bian Reconsidered

Guest essayist Nicholas Haggerty makes a provocative case for reassessing Chen’s legacy.

Summary

We’re proud to share an essay from Nicholas Haggerty, a writer and editor of the News Lens . It explores the legacy of Chen Shui-bian, Taiwan’s democratically elected president from 2000 to 2008, who eventually landed in prison on corruption charges. Today Chen is on medical parole, forbidden to make public speeches, and shunned by the party he helped propel to power.

We’ve been watching with anticipation for months as this essay has developed and taken shape, and to our knowledge there hasn’t been a piece like it, in English or in Mandarin. Why did Chen’s star never rise again, as it did for his Brazilian contemporary Lula da Silva, who was also disgraced by a corruption scandal during his presidency but is now a darling of the international left? Nick explores these questions with care. Last week he biked for six hours from Pingtung to Tainan to find Chen’s childhood home in a “village as poor and rural as any I’ve seen,” he texted us, with “not even a convenience store until Madou.”

For readers unfamiliar with Taiwan, it’s difficult to overstate how divisive Chen Shui-bian is. He’s an emotional topic, to say the least. Politics are already intensely polarizing here, but mentioning Chen raises the discussion to a whole new pitch. Like, it’s not impossible that a fistfight will break out. Even in our respective sets of parents, where the couples tend to align in their views, everyone has an entirely separate opinion of him. (We joked with Nick that we’ll almost certainly lose subscribers after posting this essay—but we implore all would-be unsubscribers to wait: we think you’ll find it to be fair and even-keeled.)

And why is Chen so divisive? For our parents’ generation, his election was a watershed moment, not just for the era but in all of Taiwan’s history. A prodigy from a dirt-poor family, son of a tenant farmer who grew sugar cane and rice, he tested into Taiwan’s top university and then was jailed for his activism and political work. He became mayor of Taipei in 1994, a landmark victory for the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), which had formed as an opposition party to the authoritarian Kuomintang (KMT) regime less than ten years before. Chen lost his mayoral re-election campaign in 1998; in 2000 he ran for president and won. He was the first democratically elected president who did not rise from the ranks of the KMT.

During his controversial two terms, Chen was criticized for provoking China in both his domestic and foreign policy. According to critics, Chen stoked tension between mainlanders and Taiwanese by refusing to adhere to the one-China policy, promoting a Taiwan-centered curriculum, and rejecting Taiwan’s historical ties to China. His defenders, in turn, acknowledged manipulation of ethnic tension, but argued that Chen was laying the path for a new future for Taiwan. Was Chen a genius, a demagogue, a hero? Perhaps all of these things, Nick suggests.

In conversations with us, Nick has voiced worry, with characteristic thoughtfulness, about writing as an outsider. Born in Connecticut and raised in New York, Nick studied East Asian history at Fordham before moving to Taipei three years ago. But to our minds this piece perfectly exemplifies to us why “outsider” perspectives are so valuable. In truth, very few “natives” would write something like this, because it’s simply too costly politically: why waste time on a lost cause? From the battles for wage equality and migrant worker rights to the softening of harsh prison sentences, political fights are fragile. They require deft, delicate maneuvering and bipartisan collaboration, and a pragmatic activist won’t waste precious capital by relitigating a divisive past. For others, unity is especially important today in the face of Chinese aggression. To write a piece like this, which advocates for a pardon, is to risk ruining your credibility on other issues—unless you’re an outsider without much baggage, naïve enough to take a position that invites vehement dissent. (For the record, Nick isn’t naïve, though he is young.) In short, this piece dares to fill a silence that’s especially notable given Taiwan’s thriving democracy.

In Part 1, below, Nick traces Chen’s legacy. In Part 2, which we’ll publish next week, he explores the corruption scandal and compares Chen’s case with that of the South Korean president Roh Moo-hyun.

Left to right: Chen Shui-bian, First Lady of Brazil Marisa Letícia Lula da Silva, and President of Brazil Lula da Silva at Pope John Paul II’s funeral mass on April 8, 2005.

Pope John Paul II’s funeral in St. Peter’s Square in 2005, one of the largest gatherings of heads of state in history, is an image of a bygone past. The main characters at the scene—Bush, Blair, and the master of ceremonies then known as Joseph Ratzinger—are long departed and missed by few, their ideas discredited in their own tribes.

The exception is Brazil’s Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, seated with First Lady Marisa Letícia. That year, Lula was in the first term of an astoundingly successful presidency: he would complete it with an 80 percent approval rating, having overseen tremendous material gains for the poorest Brazilians. Today Lula is the frontrunner to succeed the far-right incumbent Jair Bolsonaro, and is at home in European halls of government and the favelas alike.

By contrast, the da Silvas’ seatmate, visibly proud and fully in his element, is one of the many has-beens present in the assembly. But at the time, Taiwan’s president Chen Shui-bian was Lula’s peer. Both had risen from peasant families to become charismatic leaders of opposition movements against U.S.-backed dictatorships. Along the way, both did time as political prisoners. Both were founding members of the parties they would lead into power around the turn of the century—the Workers’ Party in Lula’s case, the Democratic Progressive Party in Chen’s—and, just months after their encounter in Rome, both would be drawn into corruption scandals.

This is where their trajectories diverge. The accusations Lula faced of doling out monthly bribes to congress members—the mensalão scandal—didn’t stick. He won a landslide reelection the following year. Over a decade later, after the Operation Car Wash affair removed him from the contest against Bolsonaro in the 2018 election, Lula would again live to see the other side of controversy.

Chen, on the other hand, was derailed personally and politically by allegations of embezzling government funds, money laundering, and bribe-taking. “A-Bian”— his Lula-like folk nickname—managed to finish his second term in May 2008 and hand over power to his rival, Ma Ying-jeou of the Kuomintang. By the fall, he was detained and in handcuffs, on his way to a life sentence a year later.

In prison, Chen displayed signs of physical and mental disintegration, attempting suicide several times. For two of his six years in prison he was kept in a cell of four square meters, which he shared with a fellow prisoner. (So far as I can tell, this is the worst treatment a democratically elected head of state has received in prison. Lula had a fifteen-square-meter private suite with a television, and didn’t have to wear a uniform or have his head shaved, as Chen did.) The seriousness of his decline, along with the unpopularity of Ma in his lame duck period (who granted final approval), secured Chen’s temporary release on medical parole, effective in early 2015 and renewed at three-month intervals ever since. Though he appears traumatized by his years in detention—one hand has a pronounced tremor—he has recovered his verve and clearly desires a role in public life again.

His parole conditions, however, bar him from speaking on or participating in politics, and Taiwan’s Central Election commission rejected his 2020 attempt to run for the legislature under his own party. Otherwise, though, prison authorities mostly leave him to flout his restrictions, which he does in the cheekiest ways. (As a host of a little-followed radio show, he exclusively conducts interviews so that he can plead, in theory, that he’s just asking questions. He also posts regularly on a Facebook account in the name of his deceased dog, YonGe.)

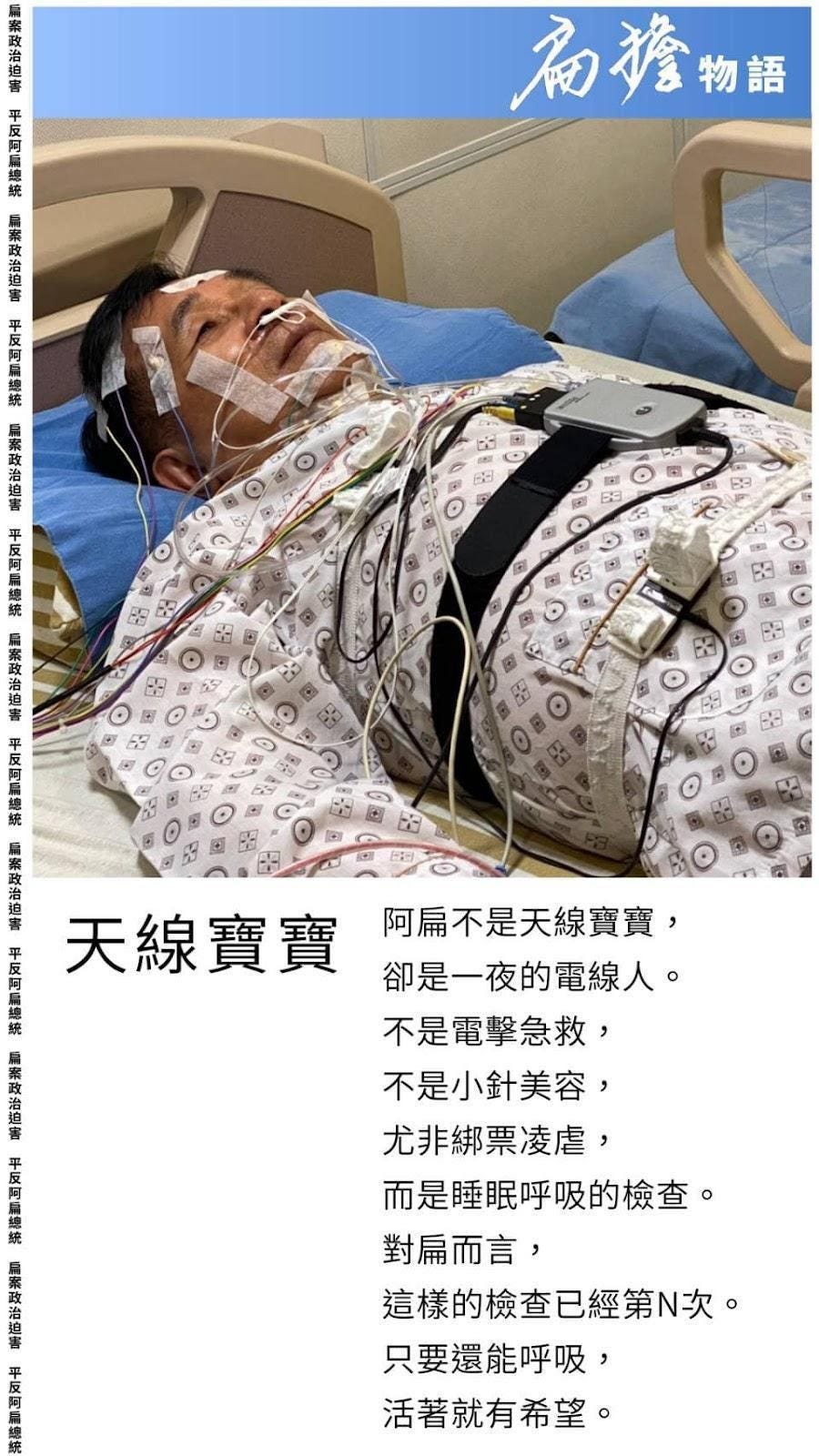

So when Chen re-enters public consciousness in Taiwan, it’s usually as the subject of tabloid and talk show outrage at his unpunished forays into politics, from speeches at fundraising events to his cheerful embraces of female admirers. Chen answers these attempts at shaming with similarly outrageous disclosures of his health scares: last May he was in the news for posting a picture of himself lying on a gurney, oxygen tubes in his nose, wires all over his temples and chest. (“A-Bian is not a Teletubby,” begins his accompanying poem.) He evidently feels compelled to prove his afflictions are real, out of indignation at the critics who believe he’s faking it, but also, perhaps, as a way to give face to the officers who renew his medical parole.

Chen posted this picture of himself on social media, alongside a poem that he wrote: A-Bian is not a Teletubby, / just a wired man for one night. / Neither an emergency defibrillation, / Nor a plastic surgery procedure, / Nor captive and in distress, / Just a test for sleep apnea. / As far as A-Bian is concerned, / He’s been through this countless times. / As long as he can still breathe, / Life still has hope.

This is an embarrassing spectacle for all involved: the media commentators who scrutinize his palsying hand, the executive branch that keeps him in this limbo, and the Taiwanese public upon whom the debate is thrust. It’s also a perplexing, sad fate for a statesman who was once not at all out of place beside Lula. A case could be made for a pardon—a presidential power according to Taiwan’s Republic of China constitution—that would free Chen and all parties from this humiliating dilemma.

The president’s office, however, has declined calls from Chen’s supporters, most recently from the city council of his hometown Tainan, to grant a pardon. It’s the expedient move, as only about 20 percent of respondents to a recent poll support such an amnesty. The party leadership is also certainly wary of his unextinguished ambitions that may turn him into what a former KMT chairman called “a wild horse off the reins.” As for Chen himself, he is treading carefully, making an effort to avoid criticizing the government.

Since coming to Taiwan three years ago, I’ve been astounded at Chen’s absence from public life. He’s a virtual nonentity among youth, but DPP voters currently in their thirties and forties recall the sense of hope they felt during his time in power, their attachment to talismans of support like A-Bian-branded beanies giving way to disenchantment when the scandals emerged.

How did it come to this? Chen’s exile is all the more peculiar in that the projects to which he was committed, Taiwanese nationalism and the rise of its electoral standard bearer, the DPP, now enjoy the broadest domestic support they’ve ever had. The DPP has more than rebounded from its post-Chen stint in the wilderness, having held the legislature and presidency since 2016. It has an especially deep backing among young Taiwanese, and a virtual monopoly on the English-language messages on Taiwan presented to the world. The incumbent president, Tsai Ing-wen, was helped along in her career by an appointment to Chen’s cabinet, and many other stars of the DPP, like Taiwan’s U.S. representative Hsiao Bi-khim, cut their teeth in his administration.

Yet Taiwan’s current social and political climate is shaped in part by policy and in part by the rhetoric and culture that formed around Chen’s administration. Facing a bureaucracy sympathetic to the KMT, and never in possession of a majority in parliament, he had a limited ability to pass legislation as president. He replaced names and symbols of China in state-owned enterprises with those of Taiwan; in a similar vein, he continued the reforms to the education system begun by his predecessor, Lee Teng-hui, to make Taiwan, not China, the basis of history curricula and civil service exams.

The five hundred thousand people who took to the streets in the Sunflower Movement, which began when young people occupied the legislature to protest a trade deal with China, passed through a curriculum that emphasized Taiwan. Even more significantly, they came of age while Chen was politicizing public life with campaigns for Taiwan’s nationhood and international status. At the forefront were his successful efforts to pass a law to allow the president to call a referendum, and his failed attempts to then use referendums to join the United Nations and institute a new constitution. The outcomes of these campaigns are much less significant in the memories of a friend who speaks of a formative childhood experience demonstrating in “Hand-in-Hand to Protect Taiwan,” summoned by Chen and Lee to form a human chain across the island in a peace rally against Chinese missile deployment.

But alongside such achievements in civic engagement, in the troughs of his unpopular second term, are moments when Chen succumbed to ugly antagonizing of arguably a third of Taiwan’s populace. “The Pacific Ocean isn’t sealed shut,” he once bellowed in a campaign speech. “If you say China is good, just go. Go and don’t come back.” The power dynamics are not equal to Trump’s telling Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to “go back”; Chen and his supporters faced political violence and the suppression of their native language by the Chinese nationalists who governed Taiwan from the 1940s. News clips of these speeches show Chen not so much as a menacing demagogue, but as defeated and full of despair.

Chen’s knack for expressing a sense of victimhood with which supporters could identify was on vivid display at a speech he gave right before the scandals began piling up. At an event to commemorate the victims of the February 28, 1947 massacre, Chen addressed the recall campaign against him, backed by the mayor of Taipei at the time, Ma Ying-jeou—glaring at Chen from the first row—over his plan to decommission a government council on mainland unification. His pleas of “Is A-Bian wrong? “Could it be that A-Bian is wrong?” are more well known today than the more inclusive, conciliatory notes he also struck.

His upbringing—he defied extraordinary odds to reach the summits—helps to explain both how he captivated people and angered the elite establishment. Chen was born into a family that he describes as “a third-level poor household,” referring to one of the lowest income tiers in the government’s welfare system. His father was a tenant farmer who harvested sugarcane and rice, and his mother and younger sister were part of a new, exploited class of workers as day laborers at a food-processing plant. His parents had numerous debts, in part to fund his education, managing them on a makeshift ledger on a wall in the family sanheyuan (a traditional Taiwanese house built around a small courtyard).

Chen’s family home in Xizhuang, Guantian District, Tainan, Taiwan. Photo Credit: Nicholas Haggerty.

Central to Chen’s conception of himself is pride in his prodigious ascent through the education system, placing at or near the top of every test and class ranking, all the way through his graduation from the law department of National Taiwan University in 1974. Just a few years later, he was one of Taiwan’s highest-paid lawyers and the youngest, he claims, in commercial maritime practice. His career to this point reflects the ambiguities of being Taiwanese under KMT rule: someone of his background, poor and Hokkien-speaking, didn’t have the opportunities afforded someone like Ma Ying-jeou, the son of a high-level party apparatchik wealthy enough to study at Harvard. But he also would have been able to continue to have his efforts rewarded, at least financially, had he stayed a more conventional course, benefiting from the prosperity of Taiwan’s “miracle” era of rapid economic growth.

In February 1980, aged twenty-nine, Chen accepted an offer to represent the famous dissident Huang Hsin-chieh in his trial following a crackdown on an anti-government demonstration known as the Kaohsiung Incident. Chen’s courtroom oratory, along with the connections he made, would launch his political career, in which he successively won seats to the Taipei city council and the national-level legislature and, by the mid-1990s, became mayor of Taipei.

Why Chen was attracted to politics, and not a more conventional path, is a mystery at the core of his personality. He gives just two clues. One is a childhood fascination with the trappings of the local-level democracy allowed by the regime. He recalls being transfixed by campaign posters and pretending to be a candidate himself. Then, at university, witnessing a speech by the dissident Huang—ten years before he would defend him at trial—inspired him to switch to the law department. Beyond this, he attests to no serious political engagement in his youth and early career. He joined the KMT as a student, essentially by default. Could his decision to defend Huang and the other demonstrators have come from a combination of his eye for the main chance, latent indignation at the injustices of authoritarian rule, and circumstance, having come of age professionally just as opportunities to run for office began to open up?

What can be said with certainty is that Chen displayed considerable bravery getting involved at this moment. Days after he took on the Huang brief, the family of Lin Yi-hsiung, another defendant, was murdered, likely by government intelligence agencies. (The facts of that massacre are well known to Taiwanese people: his twin six-year-old girls and sixty-year-old mother were stabbed to death in his home, and to this day the killers have not been identified.) Years later Chen’s wife, Wu Shu-chen, who encouraged her husband to press on after the massacre, would herself become paralyzed from the waist down in a truck accident, regarded widely by Chen’s supporters to be a state-sponsored hit job.

It was amid this extraordinary danger that Chen sought elected office, initially as dangwai —“outside of the party”—and then, when an opposition party was allowed to form, as part of the DPP. (He missed the party’s formal inauguration while serving an eight-month sentence for libel of a KMT official.) Taiwan’s democracy and distinct nationality are now wholly mundane facts of civic life. But except for a handful of elderly loyalists, Chen’s role in bringing this about is submerged in a collective memory-hole.

If Chen was so influential, why has he been forgotten? In Part 2 Nick describes the corruption scandal that overshadowed his presidency and now his legacy. He also makes the case for a pardon.

Source: https://ampleroad.substack.com/p/the-troublemaker-chen-shui-bian-reconsidered

Guy

). I’ll read it more closely later

). I’ll read it more closely later