Interesting. The study concluded: “Sustained endotheliopathy was more frequent in older, comorbid patients and those requiring hospitalization.” That is to be expected.

There are a few studies of this nature. They usually propose some drug treatments for it as well.

Does that study say that Covid actually caused the blood clotting? Or that blood-clotting was an underlying precondition, exacerbated by Covid? I checked it and really couldn’t find that info.

In any case, there are a few reasons someone might have blood clots:

1. Obesity

People who are obese are more than twice as likely to develop a thrombus (blood clot in the leg) compared with people of a normal weight. This is because obesity causes chronic inflammation and reduced fibrinolysis (ability to breakdown clots).

Chronic inflammation also happens as a result of having less nitric oxide in the body. Nitric oxide is a molecule that protects the specialised endothelium (the blood vessel’s lining) and prevents cells from sticking to the endothelial surface. Even at an early age, people who are obese have significantly lower levels of nitric oxide. It’s this reduced amount of nitric oxide in obese people that increases damage to the lining of blood vessels, in turn, increasing the risk of clots forming.

2. Smoking

Smoking increases the risk of blood clots forming by up to threefold.

As with obesity, smoking reduces the amount of nitric oxide in the body and encourages the blood to stick together to form clots. This process is driven in part by significantly increased levels of fibrinogen, an important component in clotting, present in the blood of smokers. Chemicals in cigarettes also cause platelets in the blood to stick together. Together, these factors make the blood thicker, making it harder for the heart to pump it around the body, in turn, damaging the inner lining of the blood vessels.

3. Flying and inactivity

Travelling long distances in aircraft, or being immobilised for a long period after major surgery, can increase the risk of blood clots in the form of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) – blood clots in the legs. The typical incidence of DVT is one in 1,000, but it increases up to threefold on flights longer than three hours.

Because the blood is not flowing as much, the cells and proteins in blood settle out and form clumps. When the person starts moving again, these clots can move around the body and block a blood vessel if they are not broken down. Increased body mass index, age and smoking increase the risk of developing DVT from inactivity or on flights.

4. Trauma and cancer

As many as one in four people who have had major trauma, which causes damage to blood vessels – such as if large bones have been broken – develop clots. In such cases, the clot formation is linked to both the injuries to the blood vessels themselves, as well as the often prolonged bed rest associated with treatment and recovery.

Similarly, people with cancer are five to seven times more likely to develop blood clots. This is because some cancers produce increasing amounts of coagulation factors that promote clotting. Cancer also damages healthy tissues, which causes them to swell and clot.

5. Contraceptive pill

Women taking the combined oral contraceptive pill containing artificial oestrogen and progesterone have been found to have a small increased risk of blood clots. Other oral contraceptives show similar levels of increase, with about 6-17 extra events per 10,000 women treated depending on the drug used, compared with women who don’t take the oral contraceptive.

The ingredients in contraceptives increase the levels of several clotting factors circulating in the blood, which increases the odds of blood forming clots in veins.

COVID-19

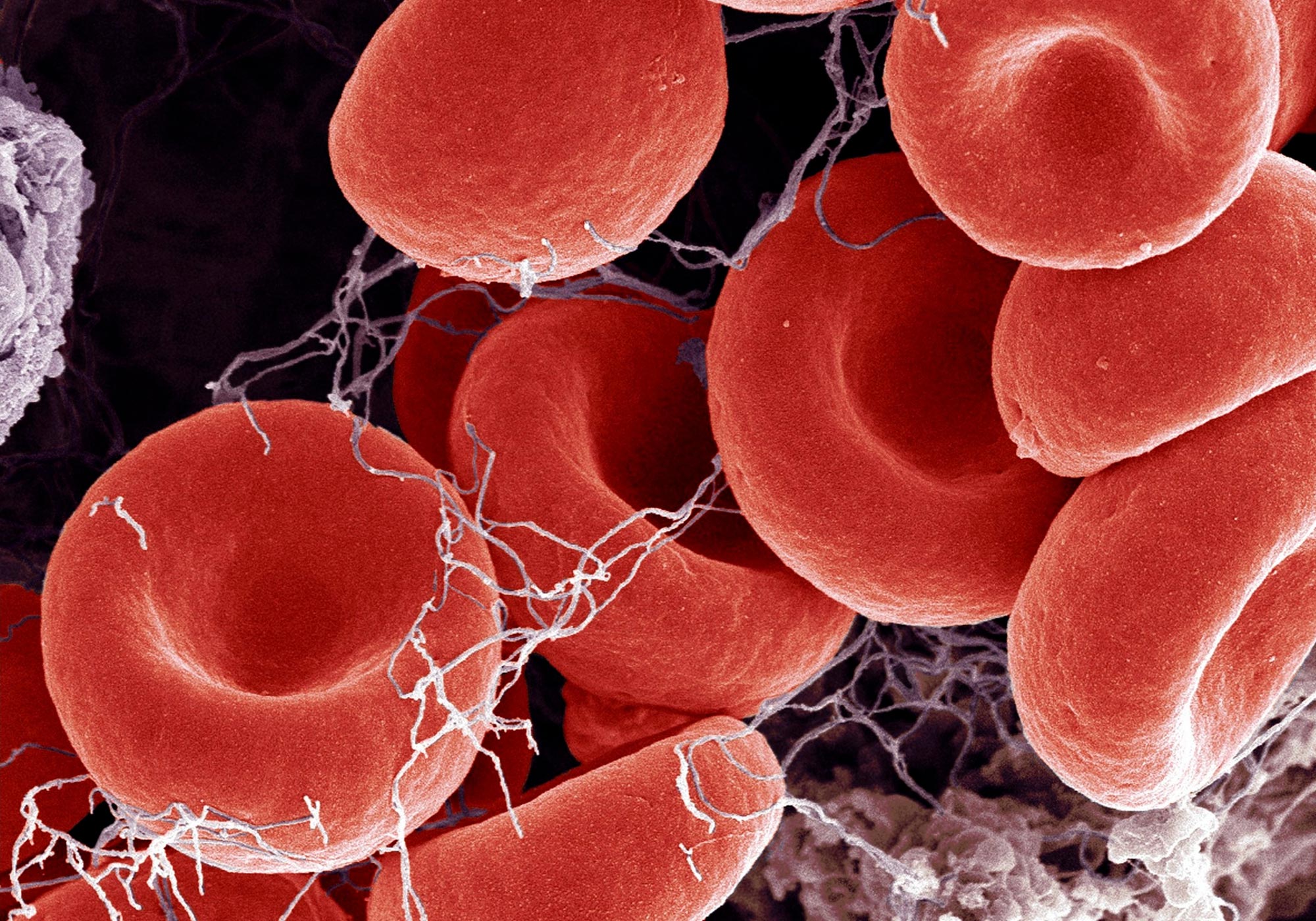

Research also shows that COVID-19 patients have significantly elevated levels of a molecule that forms when clots are present. This is because COVID-19 attacks the endothelial cells lining blood vessels, causing an increase in clots throughout the body and presenting as a vascular disease. One study also found between 2%-9% of COVID-19 patients develop pulmonary emboli (blood clots in the lungs). And COVID-19 patients are between three to six times more likely to develop blood clots in the veins compared with the rest of the population.

Other factors – such as bed rest and [age](Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY | Nature) – may increase the risk of blood clots in COVID-19.

Important to note: The prevalence of obesity among people over 60 in the US is around 40%.

Among the obese population age 51 and older, a disproportionate share — three-quarters — are age 51 to 69.

I suspect, when you combine inactivity, age, and poor diet, you’re gonna have a much higher susceptibility to blood clots, Covid or no Covid.